Why I Am Obsessed With Love Letters

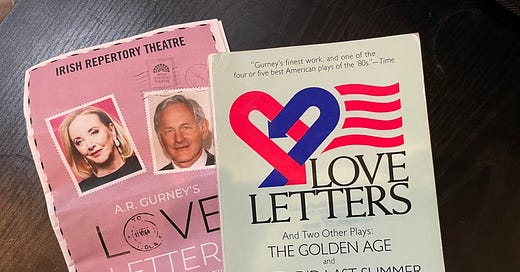

September 19th to 26th, I was at the Irish Rep Theater to see their second of three casts perform Love Letters...here is the first of two posts I shared.

First things first: J. Smith-Cameron – in the highly unlikely event that you happen to read this, please help a girl out. Being British, my daughter and I both suffer from a terrible case of “the queues,” combined hopelessly with star-stricken-ness. I wanted desperately to ask for your autograph tonight, as you were so graciously signing things for other people. I failed miserably.

As I have admitted to my students (I will henceforth be known as the professor obsessed with puppies and theater), I am going to see six of your eight performances this week. Saturday and Sunday (when I’m not escorting a small army of students), I will be front-row with my daughter and a very dear friend. If you’re signing autographs again, I am really going to make an effort to channel some American gumption and get you to sign my program. Or even my copy of the play that I had clutched under my arm!

UPDATE ON THE ABOVE: Thank you! Thank you! Apologies (again) about the sad pen!

Anyway, on to the play…A. R. Gurney’s “Love Letters” at the Irish Rep

Note: here be spoilers!

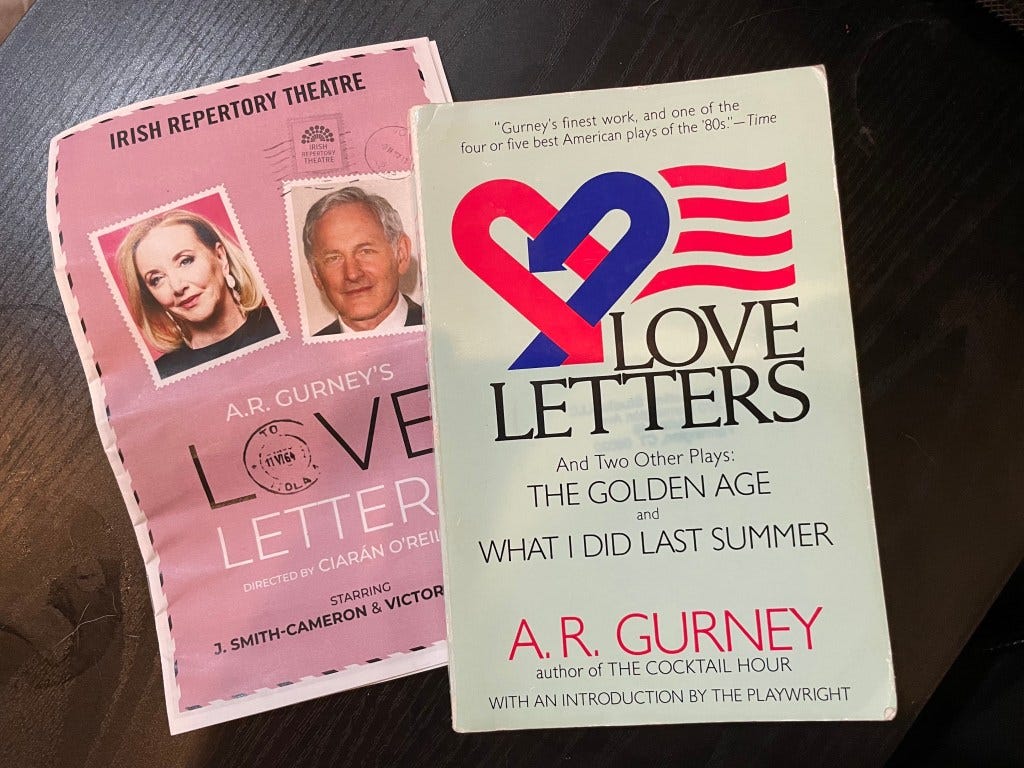

I’m embarrassed to say I don’t remember having heard of this play before. At least, I wasn’t conscious of it until I saw that J. Smith-Cameron and Victor Garber were starring in a version of it at the Irish Rep. I think I’ve actually seen the film version before, but the history of the text never registered. Since reading it, however, which I very promptly did after buying my first round of tickets, I absolutely fell in love with it. It is, as virtually everyone says, a spectacular play.

There are several things I want to say about it, though, having read it, and now having seen both the film version and an utterly amazing performance.

First, I figured out a few weeks ago why I love it so much, and it is for an oddly personal reason. My grandmother, who died a few years ago, had her own love story through letters. Hers is happier than the story of the play, but it still suggests lost potential.

When she was eighteen, my grandmother fell in love with Polly. He asked her to marry him. She said no because she wanted to pursue a university education and because her parents didn’t approve. Despite the disappointment, my grandmother and Polly stayed friends, even as he went into the navy (another parallel with the play). In the intervening years, they both married other people and had kids. Then my grandmother got divorced, and Polly’s wife died. In their eighties, my grandmother and Polly reconnected. They (re)started dating, and yes, they got married.

The relationship even saved my grandmother’s life. Not only was she deeply happy with Polly (she told me once that he was the “gold platinum standard” of men), but when she had a brain aneurysm a few months after the wedding, the doctors treating her undertook extreme measures, not usually afforded to a woman of her age. In part this was because she had just embarked upon a new chapter of her life and she had a lot to live for. In the end, they had ten years together.

Second, and personal stuff aside, I love this play because it is such a brilliant meditation on writing and communication – things that I actually teach on a daily basis. As it states in the introduction to the edition of the play that I am carrying around with me at the moment, “Love Letters,” and the two other plays of Gurney’s in the collection, “The Golden Age” and “What I Did Last Summer,” are “plays about writing” (vii). “Love Letters,” in particular, offers a keen exploration of the act of writing – both its powers and its limitations.

For Andy Ladd, one of the play’s two characters, writing is a critical outlet. As the playwright explains, “writing can be a kind of salvation for certain people” (I suspect for most of us, actually), and “it is a way of making things manageable by organizing them and putting them down in words” (vii). This play also makes me think a lot about Virginia Woolf (more on that in a minute), but her own emphasis on journaling kind of supports this point, too.

Andy, in fact, says that he writes because “I feel most alive when I’m holding a pen, and almost immediately everything seems to take shape around me. I love to write. I love writing my parents because then I become the ideal son. I love writing essays for English, because then I am for a short while a true scholar. I love writing letters to the newspaper, notes to my friends, Christmas cards, anything where I have to put down words” (29). His attachment to writing isn’t just about “salvation,” but about narrative control and fantasy.

In the opening chapter of Madwoman in the Attic, Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar ask, “Is a pen a metaphorical penis?” (3). They suggest that “Male sexuality…is not just analogically but actually the essence of literary power” (4). Citing Edward Said, they add that “the patriarchal notion that the writer “fathers” his text just as God fathered the world is and has been all-pervasive in Western literary civilization” (4). According to Said, “Authority suggests…a constellation of linked meanings… Auctorias is production, invention, cause, in addition to meaning a right of possession” (4).

Andy is not otherwise able to control the world he lives in. Subject to expectations from his family and society, he articulates feelings of constraint quite frequently: “I also have a lot of obligations,” he says, while still a teenager. He frequently mentions what his father “expects” of him, and he gestures to his mother’s hint that if he marries Melissa, he will be “set for life.” Even his name and that of his son (respectively they are the third and fourth of their name), emphasize tradition and expectation.

Recalling the failed attempt at sex with Melissa in their college days, he describes feeling as if his parents and hers were in the room: “Besides you and me, it seemed my mother was there, egging us on, and my father, shaking his head, and yourmother zonked out on the couch, and Miss Hawthorne and your grandmother, sitting on the side lines, watching us like hawks” (27). Although he clearly has rebellious episodes – hooking up with a Japanese woman, eventually having an affair with Melissa – these episodes are short-lived. Instead, Andy sustains a fantasy life for himself through writing. As he articulates, writing allows him, for a brief time, to be the “ideal son,” a “true scholar,” and a “true lover,” as he says to Melissa. Not one of these is an identity that he can actually sustain in real life, in person, which is why he retreats to his pen. He can’t live up to his parent’s expectations (who can), he becomes a lawyer, not a scholar or a writer; and he constantly undervalues his relationship with Melissa, privileging his picture-perfect life over his more complicated and demanding love for Melissa. Throughout his life, he feels “most alive when…holed up in some corner writing things down” (29), refusing to accept what he can’t control.

Andy’s tragedy, in the end, is that he cannot live long outside of this fantasy world – if at all. His actual physical affair with Melissa lasts only a few months. Afterwards, he retreats to his plain-Jane wife – the familiarity of responsibility and respectability. Even when he finally confesses his love to Melissa, it is in writing and by proxy, to her mother. He admits that he “couldn’t say [it] at her funeral,” either when he spoke during the service or after, when he talked to her mother in person. It’s a confession that Melissa thanks him for, either beyond the grave or perhaps in his imagination. She also scoffs at it – just a bit. The closest he comes to telling Melissa herself that he loves her is through the fantasy of writing: “I love writing to you. You most of all. I always have. I feel like a true lover when I am writing you.”

As for Melissa, her tragedy is that she can never get Andy to connect to her or help her in the way that she needs. Each and every time she reaches out to him, sharing her feelings or, perhaps more importantly, confessing an unpleasant truth about her life, he ignores what she has told him. He launches into some lengthy description of his school work or his sporting exploits. When she asks him for help with her husband, trying to get custody of her daughters, he flatly refuses to lift a finger, hiding behind the argument that it is a conflict of interests and an ethical quagmire. Towards the end of the play, he also ignores her pleas that he not visit her when she is back in a clinic, presumably suicidal. It’s difficult not to connect his insistence on visiting to Melissa’s death – “I’ll be gone, Andy,” she threatens, and still he doesn’t listen.

Melissa can never impose the kind of order that Andy does, either through her art or through writing, which she hates. In part, this is because the world she lives in is even more disordered than Andy’s – and more dangerous. She mentions, of course, that her mother and father are alcoholics. Her mother, in particular, appears to be an abusive drunk, going into Melissa’s room and talking nonsense at her. There’s also Melissa’s father, who disappears from her life for four years after divorcing her mother. When she goes out to California to visit him, an experience she doesn’t talk about to Andy afterward, she is dejected, feeling that she has no family, even though she can’t be much beyond her teenage years at this point.

The biggest issue for Melissa, though, is the one that she mentions only once and seemingly in passing. Her mother’s second husband goes into her room at night and “bothers” her. The victim of sexual abuse, Melissa betrays classic signs: she is promiscuous, a risk-taker, attention-seeking, and self-destructive. And this is just what we glean from her letters to Andy over the years. Her dysfunctional relationships mount up as well. She appears to marry a controlling sort of man – Darwin, who believes in “survival of the fittest” (and sorry, as a 19th-century specialist, I have to point out here that it’s Herbert Spencer who coined that particular phrase!). She turns to alcohol as an escape and hides behind the image of being “fine” with everything in her life.

Yet, Melissa does tell Andy about her stepfather, which is striking in itself. So many people don’t talk about this kind of abuse. They don’t feel safe admitting to it. She writes about it in a letter to Andy, relatively soon after her mother divorces the stepfather. She also admits, a few times, that Andy is one of the few positive influences in her life. In a way, it is part of their shared tragedy that he offers the promise of “balance.” He never realizes it because he cannot leave his fantasy world of writing. Even as Melissa repeatedly says that she wants to stop writing letters and asks Andy to stop (“I don’t want to write letters all the time. I really don’t. I want to see you” and “Won’t you please just stop writing about writing and come home and go to the Campbells’ sports party” (23), he never can. Either he cannot understand the significance of her words as an expression of need, or he doesn’t actually care to address her needs at all.

Here again, the emphasis is on Andy’s fixation with fantasy. When Andy first sees Melissa, he labels her a “lost princess.” This is also part of the title of the book that he (or his mother) gets her as a birthday gift – The Lost Princess of Oz. The irony, of course, is that she is a lost princess. He’s absolutely right. She’s wealthy – the modern-day equivalent of royalty; and she is lost – part of a dysfunctional, destructive family whose lack of care exposes her to the worst kind of abuse. Unfortunately, though, Andy coopts her into his fantasy from the very first. He’s never able to move past it to recognize Melissa as a real person. On this point, it’s perhaps most telling that he offers no reaction to her disclosures. He never probes her about her stepfather and only teases her about having an evil stepmother when she goes away to California and doesn’t write.

As my daughter pointed out, too, the two acts mirror each other structurally. In the first act, we start out with Andy writing to Melissa’s mother and identifying her as a lost princess. By the end of the act, they reach a point where they are trying and failing to forge a physical (sexual relationship). In the beginning of the second act, they’re dancing around a physical relationship, only for them both to retreat: Andy puts the romance squarely back into the realm of fantasy, begging to write to Melissa again, and Melissa retreats into her depression and mental illness, returning, as she says, to Oz and becoming again, for Andy, at least, a lost princess with a devastating finality.

Up to this point, of course, I haven’t actually said anything about the particular performance at the Irish Rep tonight. If you were looking for a review, I suppose that’s disappointing. What can I say about something so deliciously perfect, though? I am already in love with J. Smith-Cameron as a performer. I have watched everything I can get my hands on, and I think she’s just spectacular. I wrote about watching “The Year Between,” for example. I am also obsessed with theater – I really, truly am – so what can be better than watching true theater actors in a masterpiece play?

Honestly, nothing! That’s why I can’t wait to see it FIVE more times!

As to particulars, though, I loved the way that the actors played off of each other. The play direction (from Gurney himself) suggests that they not look at each other throughout the play. Melissa turns to look at Andy only at the end. Yet, the chemistry between Smith-Cameron and Garber was perfect. She was playful, flirtatious, and frustrated with him; he matched her playfulness and flirtation just enough and wove in his own brand of pretension and uneasy authority. Both actors, quite frankly, were perfect. And it was fun to watch them listening to each other, too. Perhaps that was the most enjoyable part and what made the performance for me. Smith-Cameron’s reactions, in particular, are so subtle but also just perfect for her character and the situations.

The audience was so wrapped up in the performance that there was actually a collective gasp when Andy announced Melissa’s death, and I know my students, sitting right behind me, were so wrapped up in the story that they were asking each other, in very subtle whispers, what was going to happen, very much on the edges of their seats.

[Update: FOUR more times! Wednesday night was even more spectacular than Tuesday. The rhythms and general placing were spot on…the chemistry was even more palpable. Both Smith-Cameron and Garber played up the comedy even more effectively (how that’s possible, I don’t know, but they did). And yes, I intend to continue gushing for the rest of the week.]

The last thing I wanted to say about “Love Letters” for now, circling back to the text, is how timeless and timely it is. A play about writing and communication is absolutely timeless because both of these things, art forms in their own right, are critical to how we as individuals connect with each other.

“Love Letters” makes me think a lot of Virginia Woolf’s novel Night and Day, which plays with the relationship between letters and the telephone, which was still relatively new technology when the novel was published in 1919. Unlike Katherine Mansfield, who explored the telephone as disruptive, Woolf recognized that the telephone provided a different way for people to connect with one another. It didn’t replace letters – and it doesn’t replace them in Woolf’s novel – but it does provide an alternative mode for communication and engagement, supporting a new kind of relationship. Every other communication technology, arguably, has had a similar effect. In fact, I was talking with my students about how we haven’t actually lost letter writing.

Inspired by Smith-Cameron and the States Project, I’m writing letters to voters in Virginia. In a recent training, the facilitator stressed the importance of writing by hand rather than typing. When it comes to engaging strangers, the personal touch of a handwritten letter is actually as effective as door-knocking, apparently, and way more effective than phone calls. Another of my students, who had been deployed overseas, described how he actually became closer to his siblings through letter writing, which was their only means of communication for several months.

Emphasizing the importance of personal connections, the play is also timely as everyone and sundry goes on about how AI is about to take over the world and we don’t need writers anymore. I could absolutely get on a soapbox about this one – I do, quite frequently – but I’ll leave it to A.R. Gurney to show that words convey hidden emotions and passions, they reveal secret wants and desires. In short, as this play demonstrates, they offer so much more than surface meaning that I’m not worried at all about robots replacing human writers. Robots couldn’t write love letters like this.