Tennyson’s “Maud” and H.D.’s “Eurydice”

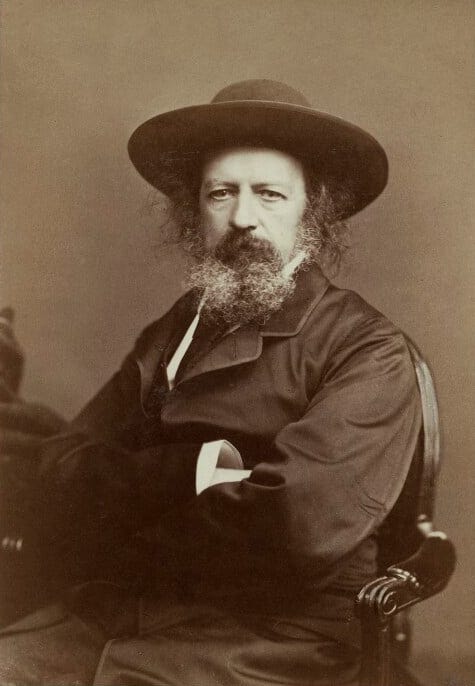

Today, October 7th, is the anniversary of the death of Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809-1892). Tennyson was the poet laureate during the reign of Queen Victoria from 1850 to his death.

Tennyson is perhaps best known today for his poem, “The Lady of Shallot,” which features in Anne of Green Gable. However, he is also renowned for producing powerful poetry about loss and mourning. In this essay, I compare Tennyson’s “Maud” and H.D.’s “Eurydice” for the various ways in which they explore images of plants, flowers, and gardens.

For more literary insights, check out our podcast and online lecture events.

Plants, Flowers, and Gardens in Tennyson’s “Maud” and H.D.’s “Eurydice”

Flowers feature prominently in Tennyson’s “Maud”[1] (1855) and H.D.’s “Eurydice,”[2] two poems that reflect on images of death and upon a disassociation between the natural world and a first-person speaker. Both poems employ flowers to stress a dichotomy drawn between life and death and between what is natural and unnatural. Allusions to different types of flowers construct a particular kind of figurative language within the poems, too: in Tennyson’s “Maud” flowers and gardens provide a vocabulary and context for the first-person speaker to reconnect to his lost love and to express his distress at his own sense of displacement. In H.D.’s “Eurydice,” by contrast, the speaker uses images of flowers to formulates her lament about Orpheus’s failed attempt to rescue her from the underworld and to articulate what she was lost because of what she calls his “arrogance” and “ruthlessness.”

Although Tennyson’s “Maud” and H.D.’s “Eurydice” were published almost three-quarters of a century apart, the two poems share a thematic preoccupation with death and they both explore death through floral imagery, including, in Tennyson’s case, through landscape. The opening of Tennyson’s poem, in fact, provides an important context for his use of flowers later in the poem because the speaker describes the first landscape in horrific terms, declaring his hatred of it and revealing an association between the landscape and the death, perhaps a suicide, of his father. The first two stanzas, describing the “dreadful hollow behind the little wood” (1), suggest that nature itself has the capacity to be distinctly unnatural or at least to seem that way to one who is in a particular frame of mind. The speaker uses adjectives “dreadful,” “blood-red,” “red-ribbed,’ and “ghastly” to articulate his horror at both the discovery of a body within “the ghastly pit” (5) and the characteristics of the landscape. Stressing a seemingly unnatural characteristic of the landscape, the speaker describes “a silent horror of blood” (3) and suggests that blood, apparently a metonym for death, saturates the landscape to the point that the “ledges drip” and “Echo there, whatever is ask’d of her, answers “Death”” (4). Although the speaker tries to rationalize his revolution when he describes how “a body was found” (5), suggesting, from the epitaph, “His who had given me life – O father! O God1” (5-6), that the body was his father’s, the verb “drip” and the speaker’s particularly graphic description of the body, “Mangled, and flatten’d, and crush’d, and dinted into the ground” (7), suggest more profound revulsion than circumstances allow.

The verb “drip” appears in “Eurydice” – “I am swept back/ where dead lichens drip/ dead cinders upon moss of ash” (8-10) –where, like Tennyson, H.D. uses the verb to suggest something unnatural in nature, playing to the word’s visceral quality. H.D.’s image is, like Tennyson’s, macabre, because of the floral references she makes. Lichens are slow-growing plants or focus that typically grow on rocks, walls, and trees. They are plants without roots. Yet, “dead lichen,” which Eurydice describes, presumably cannot continue to cling to any surface, hence they “drip” (9), logic would suggest, like “dead cinders upon moss of ash” (10). H.D.’s punning draws out two pairings, “cinders” and “ash,” and “lichens” and “moss,” that illustrate the weight accorded to images of plants and to flowers in connection to the opposition of life and death. Ash, for instance, is a type of tree but also a synonym of cinder. Lichen and moss, both plants that lack roots, connect to the notion of ashes through the metaphor and build through the association an idea that to be surrounded by ashes and cinders, to experience death in that way, is to be dislocated.

Tennyson’s use of “drip” likewise suggests the dislocation of his speaker, although it may be a more figurative dislocation: it suggests how the speaker perceives both the landscape and the body of his father as leaking into one another: blood leaks out from the landscape where the body was found and the body is violently mingled “into the ground” (7). The instability of physical forms suggested by this leaking enhances the audience’s understanding of the temporal and spatial instability that builds as the speaker meanders through and constructs a kind of hortus conclusus from his memories. The speaker’s first recollections of Maud, in fact, establishes her as a kind of plant, perhaps a flower, and the narrator as secluded garden that she has invaded. He describes her physical appearance in terms that suggest her as flowerlike: She is a “cold and clear-cut face” (1.87), the operative word being face; she is also “Pale with the golden beam of an eyelash dead on the cheek,/ Passionless, pale, cold face, start-sweet on a gloom” (1.90-91), where “golden beam,” “face,” and even “start-sweet on a gloom” suggest the flower metaphor. The g in “gloom” begins a sequence of alliteration that continues in the following lines with “growing,” “gemlike,” “ghostlike,” “garden,” and “ground,’ and the further patterns of “growing and fading and growing,” used in lines 94 and 96, and the “like” in “ghostlike,” “gemlike,” and “deathlike,” which are all characteristics applied as much to flowers as to Maud, building the metaphor from several angles within the language so that it sustains through the later narrative.

The image of flowers and of gardens expands as the narrative progresses, which makes the dearly development necessary. In Part I, as the speaker recalls his time with Maud, the apparent subject of the poem and the speaker’s love interest, it is mostly within gardens or at least in positively conceived, natural landscapes that he situates her. The gardens he associates with her are also paradisiacal, specifically recalling Eden in “the thornless garden” (1.625). In a particularly lyrical stanza, mimicking the call of birds, the speaker describes “the high Hall-garden/ When twilight was falling” (1.412-13). He also describes himself in “in our wood” (1.416), a phrase that repeats in the next stanza, “Birds in our wood sang” (1.420); [g]athering woodland lilies” (1.418). The sense of ownership, of unity (“our”), and of tranquility suggested by this description, particularly in contrast to opening of the poem, indicate how the speaker’s memories convert his impression of nature. Later, he also describes Maud within a garden of her own and Tennyson offers at least some suggestion that Maud’s body is a kind of garden in the way that the language describes her relationship to the space:

Maud has a garden of roses

And lilies fair on a lawn;

There she walks in her state

And tends upon bed and bower (1.498-502).

The alliteration of “lilies” and “lawn”, “she” and “state,” “bed” and “bower” mimic the implied unity of character and location, also inferred by the phrase, “she walks in her state” (500), where the idea of walking in a state suggests precisely the balance between the self and the external space. Roses and lilies have specific connotations, too, with Victorian floriography perhaps compounding their significance: roses are associated with the Virgin Mary, with the goddess Venus, with purity, and also with martyrdom and mourning.[3] Lilies indicate beauty, innocence, and virginity.[4] The symbolism of both flowers applies to the speaker’s perception of Maud. Other references to gardens, “the garden in the turrets/ Of the old manorial hall” (2.219-20) compound the impression that it is a secluded and secure place that the speaker imagines and one that specifically allows for his removal from the outside world that he finds uncertain and threatening.

The word “flower” and several specific types of flowers serve as expressive devices in the development of this impression, too. In “Maud,” the first use of the word “flower” occurs at 1.126, when the speaker philosophizes that “We are puppets, Man in his pride, and Beauty fair in her flower” (126). Following the end-line semicolon, the speaker asks, “Do we move ourselves, or are we moved by an unseen hand at a game/ That pushes us off from the board, and others ever succeed?” (127-8), associating the image of the personified concept of “Beauty” with a problem of agency: the speaker seems to wonder whether the pride of “Man,” capitalization suggesting generalization, is a natural state, like the placement of “Beauty” specifically “in her flower” (126), with both the preposition, “in” and the possessive pronoun, “her,” stressing the conceptual relationship between beauty and flowers that is important to the speaker’s analogy and rhetorical argument. Flowers are not exclusively pleasant and good, though: just as the speaker initially suspects Maud of dishonestly, calling her cold when he first describes her, he equates “the cruel madness of love” to the “honey of poison-flowers and all the measureless ill” (1.156-57) when he calls Maud “unmeet for a wife” (1.158). “Passion-flower” (1.485) is the next instance of the word’s usage, however, and it traces the development of the speaker’s remembered perception of Maud, how he begins to see her as a desirable object. Notably, the speaker imagines a “lion” within Maud’s “garden of roses” that is “claspt” by the passion-flower as he himself “stood by [Maud’s] garden-gate” (1.495). Although the image of a lion might seem threatening its symbolic association is also with the Resurrection and in other classical literature, it suggests fortitude. When Tennyson repeats the term “passion-flower” at 1.909, it is in one of the poem’s more lyrical sections, as the comparison between Maud and the image of the flower, specifically a rose, has collapsed entirely and she is “Queen rose of the rosebud garden of girls” (1.902) and “the passion-flower at the gate” (1.902) lets fall a “splendid tear” (1.908), apparently in a state of happiness, as “splendid,” although it also suggests something that might simply be remarkable, more obviously indicates something that is quite glorious and special.

In much the same way that Tennyson builds a dual connotation for floral imagery in “Maud,” using flowers to signify both a positive and vibrant state and to create a sense of morning and loss, H.D. also uses flowers throughout “Eurydice” to tease the poem’s distinction between life and death. Eurydice speaks of wanting to have “slept among the live flowers” (4), and gradually this seems to emerge as a metaphor for her burial within the earth. She repeatedly refers to flowers, however, repeating the word twelve times and frequently within the poem’s rhythmical sequences of repetition, such as in the third section, where the word “flowers” repeats and becomes a signifier of something like a lost soul or the innate beauty of the world that is lost (“all the flowers that cut through the earth,/ all, all the flowers are lost” (53-4)). The word and the image gradually develop, though, to become an expression of earthly, natural beauty and specifically lost beauty: “blue of the depth upon depth of flowers,/ lost” (64-5). They also come to signify in themselves what Eurydice longs for: “flowers,/ if I could have taken once my breath of them” (66-7). The sequence of hypothetical statements, “if I could have,” runs for two stanzas, the allusion to flowers repeated with “if I could have caught up from the earth/ the whole of the flowers of the heart” (73-4) but reaches a conclusion (“I could have dared the loss” (81)) that provides a final emphasis of the possible solace of beauty and nature. The verb “dared,” however, and the sense of “daring a loss” (81), coupled with the idea of catching up, even breathing in the beauty of the flowers, complicate the value that Eurydice perceives in life. The idea of daring recalls the actions of Orpheus and the conventional interpretation that he acts out of love and bravely. Yet, Eurydice says that if she had experienced beauty, she would have “dared the loss,” suggesting that she would have chosen to give up the “flowers of the earth” if she had ever once possessed them. The reference to “blue crocuses” also invokes the garden of Flora and the Ovidian character, Crocus, who, from impatience, transforms into the flower that bears his name, suggesting perhaps the idea that the flowers have a dual symbolism; they should, perhaps, have served as a reminder of the dangers of impatience.[5]

Through continued allusion to flowers, Eurydice reaches a state of peace, too. She begins to realize, towards the conclusion of the third section of the poem, that, because of the “arrogance” of Orpheus, “[h]ell is no worse than [his] earth” (100), an idea that she repeats with an emphasis on “my hell” (106). She realizes, too, that the loss of Orpheus’s flowers, “your flowers” (103), is no not a loss either. Although Orpheus can “pass among the flowers and speak/ with the spirits above earth” (108), Eurydice concludes that she has more “fervour” (110) and “more light” (114) having “the flowers of myself” (122). The poem’s narrative thus works towards a point at which Eurydice can perceive her own worth and articulate the problem in the way that Orpheus has engaged with her in the past, the flowers of the poem thus providing an emblem for Eurydice’s feelings.

Both Tennyson and H.D. employ flowers as symbols within their poem and each allow the symbolism to develop over the course of their poetic narratives. Whereas Tennyson develops the value of flowers, though, in connection to his speaker’s perception of Maud as a desirable object, H.D. maintains a persistently positive association with flowers, developing instead her speaker’s relationship to them, leading to Eurydice’s realization that she has “the flowers of myself” (122), a kind of internal integrity and value, that allows her to overcome her sense of isolation and her bitterness at the actions of her husband.

[1] Tennyson, Alfred. “Maud.” Tennyson: A Selected Edition. Ed. Christopher Ricks (Harlow, UK: Pearson Education Ltd, 2007), pp. 511-582.

[2] H.D. “Eurydice.” H.D. Collected Poems: 1912-1944 (New York: New Directions Books, 1983), pp. 51-55.

[3] Hall, James. Hall’s Dictionary of the Subjects and Symbols in Art (London: John Murray, 2001), p. 268.

[4] Ibid, p. 192-3.

[5] Ibid, p. 125.